The Prague Jewish Ghetto Destruction

On this post I’ll seek to give you an overview of the timeline and decisions taken which eventually led to the destruction of the Prague Jewish Ghetto. Before the year 1437 Jewish citizens in Prague could live wherever they wanted and there is ample evidence to show that they had communities all over what we now call the Prague 1 district. In 1437 the first of the Habsburgs, King Albert took the throne and one of his first decrees is to establish an area in the city by the riverside where Jewish citizens would now have to live. It was not a great place to stay especially in ground floor properties which were regularly flooded. I describe several of the lost places in the Prague Jewish Ghetto on my Old Town and Jewish Quarter Walking Tour.

Many Old Town buildings were destroyed during this redevelopment process. This picture shows the rear of the ST Nicholas Church on the Old Town Square and the photographer Karel Bellmann would have been standing two blocks away at the location of the Old/New Synagogue. To get this picture now, you would have to demolish two whole blocks of some of the most expensive property in the city. The Benedictine Monastery at the back of the church belonged to the Old Town and was also destroyed.

Is the Prague Jewish Ghetto and Josefov the Same Place?

The Prague Jewish Ghetto stood in an area roughly to the north of the current Old Town Square. It was not a defined area and did not come under the rules of the Old Town. Josefov is an official district defined in 1849 which covers largely the same area as the old ghetto. From 1849 to 1896 Josefov and the Prague Jewish Ghetto were the same place. Photos and pictures exist of individual buildings but it’s difficult to describe what the Prague Jewish Ghetto looked like as an area so I strongly recommend that you visit the City Museum next to the Florenc metro station and take a look at Langweils Model, built between 1826 and 1834 it’s the only 3D record of the time. Tip: take a city map with you.

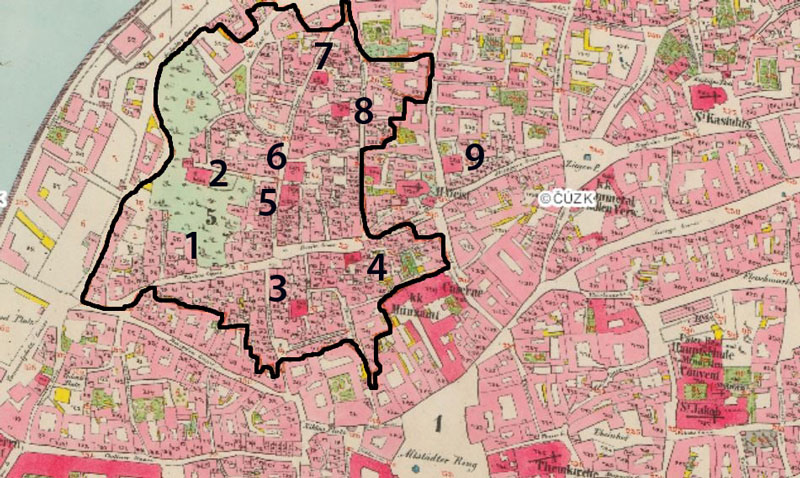

1842

The picture shows the boundaries of the Prague Jewish Ghetto in 1842 and the white area bottom/centre is the Old Town Square. There are a couple of things to note. I’ve numbered the synagogues that were present at that time and would remain up to the 1890s.

- Pinkas Synagogue

- Klausen Synagogue

- Maisel Synagogue

- New Synagogue

- High Synagogue (not open to the public)

- Old/New Synagogue

- Great Court Synagogue

- Gypsy Synagogue (where Franz Kafka had his barmitzvah)

- Spanish Synagogue

The reason that number 9 is in an area of it’s own is because the Prague Jewish Ghetto had both Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jewish communities. The Sephardic part around the Spanish Synagogue was separated in the ghetto but was included in the Josefov district.

1849

We got a new Emperor in 1849 called Franz Josef. He immediately defined the Prague Jewish Ghetto area as the 5th district of Prague and gave it his name, Josefov. The effect of this was to allow all Jewish people free movement again (not just the wealthy ones who had been able to buy themselves out of the area), the first time since 1437. Much of the Jewish community moved and the area, as bad as it was, rapidly declined becoming the home for the poorest in the city whether they were Jewish or not.

City Planning and Statistics

For the next 50 years the city will examine itself. During this time it would demolish 95% of the defensive city walls and it would expand so it’s easy to see how city planning was getting important. Planners were looking at:

- The layout of the streets should take into account prevailing winds.

- The height of the building should be in proportion to the width of the associated street.

- Residential spaces and courtyards should reflect the population in a built-up area.

- The expansion of the electric network for municipal purposes including public transport and city lighting.

- Industry in the city should not negatively affect the health of the population.

- That there be systems for supplying potable water and the removal of effluent.

Statistics were being gathered all over the city looking at housing capacity, mortality rates and environmental controls. Statistically on the basis of mortality, hygiene and housing overcrowding, Josefov was easily the worst area in Prague. In a time of great leaps forward for architectural and city planning in western Europe, Josefov and parts of the Old Town were described as Medieval.

The Sanitation Laws

Act 22 and Act 23 were passed in 1893 to provide a legal and financial framework for the city to designate the areas to be redeveloped and acquire the necessary land/properties. These were divided into 38 sections and would be called the Remediation Districts. People frequently ask me if it was a deliberate act against the Jewish people so let’s be clear, of the 380,000 square metres to be redeveloped, the Prague Jewish Ghetto accounted for a little under a quarter at 92,984 square metres.

December 1896

Agreements for sale were being negotiated and land was being expropriated where necessary. Records show that eventually, 260 residential buildings and 3 of the synagogues in the Prague Jewish Ghetto would be destroyed. That number 260 bothers me. This was the number of properties either bought or expropriated but it wasn’t the number of buildings demolished because the problem in the Prague Jewish Ghetto, what we call “Black” buildings, built without permission, uninsured, untaxed and unrecorded on maps. The city had an area to buy, if a building was unrecorded then it did not have to be bought.

18,000 people would be displaced between 1896 and 1920. The process begins with the acquisition of 4 of the 38 sections which are then cleared of people and then a strange thing happens.

On December 1st 1896 there were 23 properties in the Josefov district that had been acquired. On Sunday 6th and Sunday 13th of December it was recorded that tour guides took almost 2400 people through the back alleys of the Prague Jewish Ghetto to explore these buildings. Entrepreneurs sold candles to people before they went inside. The Benedictine Monastery behind the ST Nicholas Church on the Old Town Square was also marked for destruction and became a tourist destination until that Christmas.

Heritage

One of the lesser known things that Emperor Franz Josef did when he took power was to set up the Central Commission for Research and Preservation of Architectural Monuments with a view to passing a law called the Austrian Monuments Act. Unfortunately it never became law. Then in 1893 when the Sanitation laws had been passed to begin the redevelopment process, a “Prague Monuments Commission of Inventory” was also set up. It’s role was city-wide and identified items of an “historic or artistic nature” that could be lost. They could submit reports and make recommendations to the city but they could not block or reverse a demolition order. Therefore the most that could be achieved was a visual record so their work was restricted largely to arranging for a pictorial and photographic record of the Prague Jewish Ghetto. The official record of the area was made by Jindrich Eckert (Photographer). Jan Minarík (Oil paintings) and Václav Jansa (Watercolours).

But for a lot of part-time researchers like me there are two other people we have to thank. The first was Zikmund Reach. He was a Jewish bookstore accountant, stamp collector and hobby photographer. The second was Karel Ferdinand Bellmann, a third generation bell ringer and bell maker. Great name eh! but curiously born in Czech (where bell is “Zvon”) who only spoke German (where bell is “Glocke”) and of Swedish heritage (where bell is “klocka”) so only in English does his name give sense. Both of these men owned or ran bookstores and printed/published postcards from their photographs to sell so it’s their pictures that you commonly find when you look for historical photos of the Prague Jewish Ghetto.

The other thing to remember is that photography was an expensive business so you had to have a pretty good reason for taking pictures. We are lucky that several of the photos in the Jewish Ghetto (including the Pinkasova Street picture above – I show you where this street used to be on the Old Town and Jewish Quarter Walking Tour) were paid for by the man in the pictures. Mr Lehky in the foreground centre of the street was the builder who had the contract to demolish the buildings so he was recording what he was about to destroy. Cool, in a sad kind of way!

Something Related or a Few Minutes Away

Paris Street – Rebuilding the Jewish Quarter

Memorial – Pinkas Synagogue National Holocaust Memorial

Attraction – Jubilee Synagogue

Attraction – Spanish Synagogue

Attraction – Old Jewish Cemetery

Activity – Old Town and Jewish Quarter Walking Tour