Paris Street – Rebuilding The Prague Jewish Quarter

Before you start this post be sure to read Why the Prague Jewish Ghetto Was Destroyed. That post explained the reasons for the demolition. This post starts in 1887 with the plan for the rebuilding of the Prague Jewish Quarter into what you see today. Of all the streets in the fifth district or what we call Josefov, Paris Street is without doubt the finest example of a street that blends neo-Classicist and Avant-Garde styles. If you are exploring the area and will be going into the synagogues then take a look at the Skip the Line Tips and Tricks post for some time saving tips.

Who Paid For All This?

On my Prague Architecture Walking Tour it’s not long before the question comes up about who paid for all these buildings. Back in 1893 the city had come up with a rough plan:

1) The city identifies “Remediation Areas” for redevelopment (Remediation is loosely defined as “the correction or remedying of something that is corrupted or deficient”).

2) The city takes bank loans to buy the associated land/property.

3) The city divides that land into 38 sections for building and sells the land/property at a profit to developers to demolish and rebuild according to new building codes.

4) The city uses the profit to pay for city infrastructure.

Ha! Ha! of course it’s never that simple is it. Banks refused to offer loans, developers were interested in some plots of land but not all. One of the biggest delays was the refusal of the city to allow developers to negotiate a price with private owners so a plot of land could not be redeveloped until it was owned by the city. If the city asked too much, the developer would instead build in another area like the New Town etc but eventually the process worked, the land was sold and the building began. It was done in several stages. So to answer the question, it was the city who paid for the land to be available but it was the developers and private individuals who paid for the buildings that you see now.

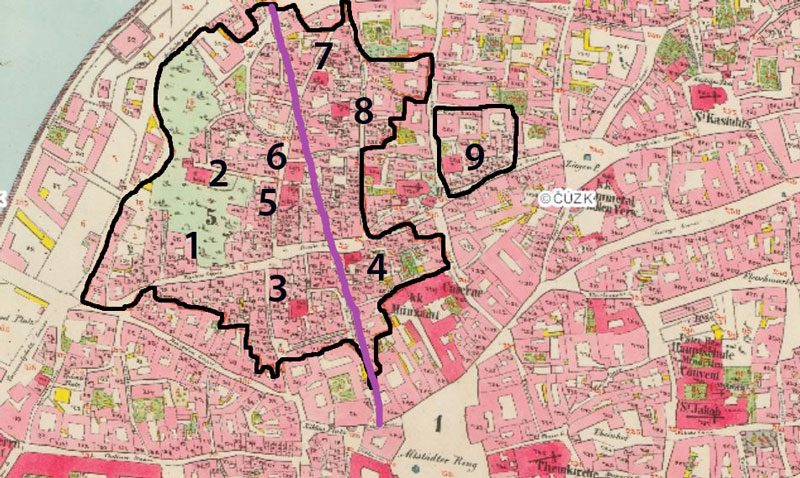

The picture above shows what the Jewish Ghetto boundary was in the 1840s and how the new street would go right through the middle of it. The bottom of the purple line is the Old Town Square. The top is the river Vltava. The numbers represent the locations of the 9 large synagogues in 1842 so if you want to know what was where please read the Destruction of the Prague Jewish Ghetto post.

Before Paris Street

So they knew the layout of the streets but what they didn’t yet know was what the new buildings would look like. There had been a small street here called Mikulašska which translates as “the way to ST Nicholas” (the church on the Old Town Square was at the end of that street) but in the new plan all the houses on either side were to be demolished to make way for the new boulevard which still had the name Mikulašska until 1922 when it was renamed Paris Street. It was not the first street in the city with that name. The original Paris Street ran next to the current Hotel Paris (hence the name) but was renamed to “at the place of the Municipal House” in 1912. The purple line in the picture above just gave you an idea of where the new street would be located. The picture below gives you an idea of the level of destruction caused by the demolition taking place that will create Paris Street. You are looking towards the river and the tower centre-left is the Jewish Town Hall. The house centre-top is where the Hotel Intercontinental is located today.

Back on April 5th 1896 a man called Vilém Mrštík published a damning indictment on what was being planned by developers and against the city’s vandalism of it’s heritage. If this was just one man then no problem. But it was a problem because dozens of people including writers, architects, artists and more importantly, government ministers rallied against the more “unsubtle” plans. The effect was to set up a special “Art Commission” consisting of, amongst others, Classicists (Zitek and Schulz) and Modernists (Fanta and Ohmann) which would directly input into the planning process. On November 12th 1897 they submitted their proposals for changes to be made to the plan to support city heritage. These were rejected and the Art Commission resigned a month later. A National Monument Act 22/1987 was only passed into law on January 1st 1988. So fortunately what we have today is a blend of styles.

Classic Versus Modern

As the 20th Century began, to be an architect in Prague was to be somebody whose work would be admired for the next 100 years and more. But you still had to get your planning application granted. The great argument raged about whether buildings should copies of previous styles i.e. Classicist in which case you favoured neo-Baroque, neo-Gothic or neo-Renaissance. Or would the Modernists at the forefront of breaking new styles like Secession and Art Nouveau prove more popular.

Initially it looked like the Classicists would win the day as the early new buildings bordering the Old Town Square had a very Baroque look but it later turned out that this was part of the city planning requirement for specific buildings. Also the big state projects in the 1880s like the National Museum, National Theatre, Decorative Arts Museum, Rudolfinum and many banks were built in the neo-Renaissance style.

But when given free rein, the private individuals and developers in the Prague Jewish Quarter, give or take a few historic exceptions, went almost totally on the path of the Modernists which gives the fifth district of Josefov and especially Paris Street it’s Avant-garde appearance.

Take a walk along Paris Street and never will you see part of a city with an apparently similar look with so much creativity and individualistic detail. I give you a taste of what you are looking at and some of the architects involved on the Prague Architecture Walking Tour. Any building on a street with a Josefov address is considered to be in the Prague Jewish Quarter.

What Happened to the People Who Lived Here?

When we talk about who lived here before 1896 we are largely talking about poor tenants and lodgers. Even if members of an owners family were still living there, most owners had already left. 80% of the old Jewish Ghetto was purchased with an agreed seller price to compensate the owner. 20% of properties had to be expropriated. Initially the city believed that it would have to build in other areas to accommodate the 18,000 displaced residents but when it became clear that the redevelopment process would take a couple of decades, the movement of people was gradual and ghetto residents simply moved to wherever they could afford.

Do Jewish People Still Live Here?

1849 saw the first exodus, 1938-40 the second and we all know what happened after 1941. One or two buildings in the Prague Jewish Quarter have a very Jewish appearance with detail like in the picture above which you can see from Paris Street but which is actually in Maiselova. Statistically, less than 0.5% of people who live in Josefov identified as Jewish in the last census. If you come to the Prague Jewish Quarter expecting hat shops and delicatessens on every corner then you’ll be disappointed. Today Paris Street is part of an historic Jewish Quarter with many stories that guides like me love to tell.

Paris Street Today

Regardless of the architecture or the history, the main reasons for visiting Paris Street today are that you are using it to get from the Old Town Square to the river to see the Prague Metronome. Or you are coming for the high-end shopping as this street is where you’ll find the top brands like Jimmy Choo, Cartier, Prada, D&G and many others.

Something Related or a Few Minutes Away

Attractions – Old/New Synagogue

Attractions – Spanish Synagogue

Attractions – Old Jewish Cemetery

Jewish Prague – Journey of a Torah Scroll

Prague Architecture Walking Tour

Old Town and Jewish Quarter Walking Tour