Thomas Vokes and William Greig, Scottish Heroes of the Prague Uprising

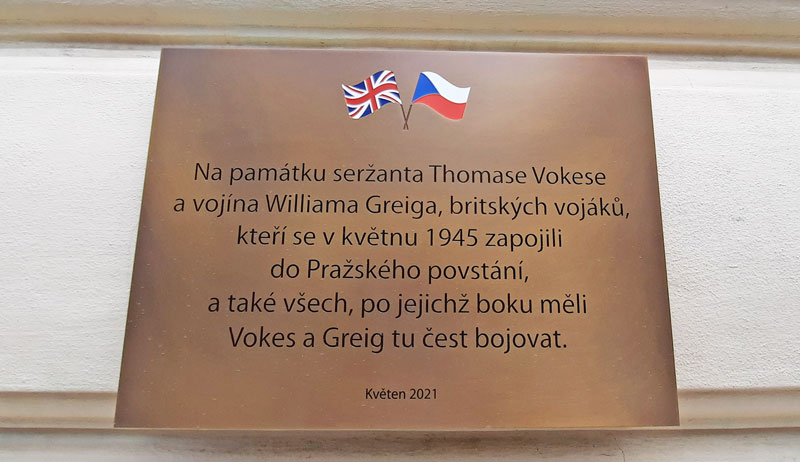

On May 5th 2021 a memorial plaque was unveiled at the Na Smetance primary school in the Prague 2nd District of Vinohrady. Strangely it commemorated two British soldiers called Thomas Vokes and William Greig who fought with the Czechs during the Prague Uprising exactly 76 years earlier. For many publications that’s about all they reported except for who attended the ceremony. As usual I thought I would dig a little deeper. It’s the story of sacrifice, bravery, luck and a big bluff.

How the Story Was Unearthed

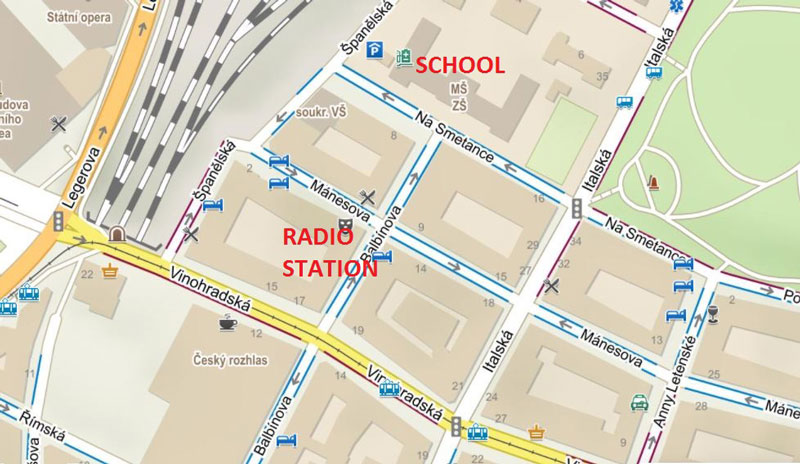

In 2012 a Czech amateur historian called Stanislav Motl was researching the events at the Cesky Rozhlas radio station during the Prague Uprising which was between the 5th and 9th of May 1945. He’d stumbled across a father/son from the Kopecky family (the father was an architect and his son was a Staff-Captain in the Czech army) and in correspondence he’d discovered that they fought at the radio station with two British soldiers. Initially Stanislav Motl could not understand the British connection and it was only after contacting the Kopecky descendants that he received further documentation which detailed the actions of soldiers in the surrender of an entire SS detachment.

The Scottish Connection

So the first new information was that these men were Scottish and I learned how they became POWs. The story starts in 1939 when two men from Scotland joined the army and that was Thomas Vokes and William Greig. For the purposes of the story I’m going to be mentioning William Greig more because quite frankly, more has been written about him over the years. Both men were part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) sent to France in 1940 to assist the French army. I can say for sure that William Greig belonged to the 51st Scottish Gordon Highlanders but I can only guess that, being Scottish, Thomas Vokes may also have been in the same regiment. In any case their military career did not last long as both men were cut off from the retreat from France and became prisoners of war in June 1940.

Picture Credit: Press and Journal

1940-1944

Taken from their place of surrender at the beach close to the French town of St Valery-en-caux, Thomas Vokes and William Greig were marched across France and Belgium to Holland where they were transferred to trains and taken to Stalag 8a prisoner of war camp close to the German town of Gorlitz and about 20km from the Czech border. Despite their status as prisoners of war they had to do hard labour at the nearby Konigswalde quarry. It was during a night march from this quarry back to the camp that William Greig, Thomas Vokes and two others made their escape.

In the winter of 1944/45 Private William Greig (aged 21, he’d lied about his age and joined the army aged 17) and Sgt Thomas Vokes foraged for food and drink while drifting through the area that we now call Bohemian Switzerland. They took chances by entering small border villages in the Protectorate (what Czech was called in WW2). Hiding in a cemetery they had a stroke of huge good fortune to make contact with “friendly Czechs” and were able to communicate in basic German.

Over the next couple of months they would work their way south towards Prague until they reached the Melnik area about 30km north-west of the city where they meet the Mužík family. It was this family that, at great risk to themselves, arranged for William Greig and Thomas Vokes to be transported to Prague and connected to the city resistance.

May 1st 1945

On or about May 1st 1945 our two Scottish soldiers arrive in Prague just as rumours are spreading that the Russians are on the outskirts of Berlin. Barely having arrived in the city they were quartered in a safe house close to the New Town Hall when Prague begins to boil over and on May 5th the resistance attempts to take over the Cesky Rozhlas radio station. Greig and Vokes volunteer for service to help the civilians however as trained soldiers, the resistance makes better use of them for the assault on the radio station. A witness at the time said it was “good to have experienced soldiers” on their side unaware that Greig and Vokes’ combat experience was measured in days. Both of them stayed on to form part of the guard for the Radio station.

The Radio Call

Having taken over the radio station by the afternoon of the 5th the occupants were then attacked on three sides by heavy weapons and aerial bombardment. One of the reasons that William Greig is better known comes from a radio broadcast that he was asked to give on the evening of May 5th from the Cesky Rozhlas radio station calling for help from allied forces. You can hear 42 seconds of the actual broadcast on the video above.

The Na Smetance School

The school was used as a small barracks for 123 SS soldiers mainly because of it’s location overlooking the railway station but it was also just one block from the radio station.

After overcoming Nazi resistance at the radio station and building street barricades to stop reinforcements getting through it was beginning to look quite good for the Czechs and then reality struck home.

There is a famous photograph taken outside the radio station on the corner of Vinohradska and Balbinova on the afternoon of May 5th. It shows five civilians sprawled across the road and pavement and all dead. This was the result of the SS soldiers one block away at the school firing a heavy machine gun directly down the street into that junction. Basically for the next two days there was a stalemate with the Czechs not able to attack the school but the SS not able to break through to the radio station.

The May 7th SS Surrender

There were other things happening on May 7th that the Czechs at the radio station were not aware of like, 1) The Red Army were pushing the Nazis south so a lot of retreating German tanks and armoured equipment were heading their way. 2) non-Communist Russians who had joined the fight on the 5th were now retreating west because 3) They’d found out that the Americans were not coming to Prague. So what happened next was in supreme ignorance of the overall state of the city-wide battle.

The plan that William Greig and Thomas Vokes put forward was simple. Dress the two British Soldiers as smartly as possible (considering they’d spent 4 years in a labour camp I expect there was a bit of sewing involved) and with two Czech commanders (Kopecky and Zaruba, Zaruba was killed by a mortar the following day) they would approach the school under a white flag.

You could be mistaken for thinking that standing in the street asking the heavily armed SS to surrender was worth a medal. Actually then going INSIDE the school and sitting down with the SS commander probably was going to be a posthumous medal. But in a sign of outstanding bravery, in they went. Greig and Vokes pushed the story by saying they were representatives of the King and Thomas Vokes gave the ultimatum “Surrender or be bombed out by the end of the day”. The SS soldiers surrendered and gave up their weapons although I’ve never found out what happened to them other than they were given safe passage west towards the town of Beroun. I wonder if it wasn’t the threat of bombing so much as knowing that the Red Army was almost in Prague and that the SS would not fair well that the commander was looking for a way out.

The Aftermath

On a city-scale this whole event was treated like a skirmish. Hundreds of civilians had already died in the initial uprising and hundreds more would die on the 7th and 8th as the Nazis sought to regain some kind of control in the city. Basically the uprising was all but defeated until at the last hour it finally became widespread knowledge that the Red Army would be entering the city the following day May 9th (read the story about Ivan Goncarenko) two days earlier than originally planned. So unless they were part of the rearguard action then the German retreat to the west began.

The Awards

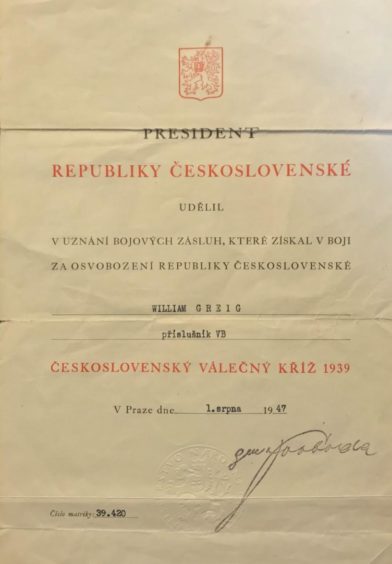

William Greig was awarded the “Czechoslovakian Military Cross 1939”, sometimes called the Czech War Cross, on August 1st 1947. He didn’t actually get informed about it until 2nd April 1948 due to another William Greig being notified in error. The person who signed off on the award was none other than General Ludvik Svoboda who would become the President in office at the time of the 1968 Prague Spring. I have to assume that Thomas Vokes also received the same award but I’ve not been able to confirm it.

It reads “the President has granted to, in recognition of the combat merits gained in the struggle for liberation of the Czechoslovak Republic, William Greig”

Then underneath is an interesting line: Príslušník VB

As Príslušník translates as “member” then VB is interpreted as Velka Britanie (Great Britain) or simply a member of the British Armed Forces.

Picture Credit: Press and Journal

The Czechoslovakian Military Cross

It was the Czech Government in exile during WW2 in 1940 that first designed what was called the Second Czechoslovakian Military Cross (there was already a Czechoslovakian Cross 1918) so any awards given from 1945 were not ratified until after the new government was elected in 1946 and it continued to be awarded after the 1948 Communist Coup. It could be awarded to anybody who had performed meritorious action in the liberation of Czechoslovakia as long as they were in the military.

Other awardees include General George Patton, Dwight Eisenhower and Georgy Zhukov. The front (obverse) side shows the National symbol of the two-tailed lion. The reverse side is more interesting because it contains the symbols that you would have found on the Czechoslovak Heraldic Standard at the time. The two-tailed lion is centre but surrounded by the numbers 1, 9, 3, 9 and represents Bohemia. On the points of the cross, at the top is Slovakia (double-bar cross), left is Moravia (red and white blocks), right is Silesia (black eagle) and bottom is the far eastern part called Carpatho-Ruthenia (upright bear with blue/yellow stripes which is in present-day Ukraine).

This medal could be awarded to a recipient more than once and Czech Soldiers fighting on the Eastern Front are an example of this. If the original cross was re-awarded then the figure of a Linden Branch could be attached to it. Only the person who was awarded the cross could wear it. The medal was made obsolete on January 1st 1993 when the country split in the Velvet Divorce and the modern equivalent is the State Defence Cross.

Something Related or a Few Minutes Away

History/WW2 – Winged Lion Memorial (Czech/Slovak air crew)

History/WW2 – Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

History/WW2 – The Beneš Decrees

History/WW2 – Operation Anthropoid

History/WW2 – The Prague Uprising

History/Culture – The Linden Tree

Food and Drink – Riegrovy Sady Beer Garden

Art and Culture – Theatre Le Royal