Prague History – World War Two

Remember that I do my own World War Two walking tour which covers all of the events as it affected Prague from 1938 to 1945. It includes central characters like Kurt Von Neurath, Reinhard Heydrich, Karl Herman Frank and Adolf Eichmann. It shows you and explains various memorials, it explains the life and destruction of the Jewish population, Operation Anthropoid, the Prague Uprising and pictures from the past.

World War One – End of Empire | The First Republic | World War Two | Liberation – Post War Changes | Socialisation – Communism Takes Hold | The Prague Spring | The Velvet Revolution | Czech Republic Today

Barely 6 months after the signing of the Munich Agreement, Czechoslovakia, minus its border regions and known as Bohemia and Moravia was occupied by the Nazis. President Edward Benes had stepped down and been replaced by President Emil Hacha. Slovakia had ceded from Czechoslovakia the day before on March 14, 1939 to form an “independent” fascist state and thus very short work indeed was made of the former Czechoslovakia. Overnight, everyone had to start driving on the right side of the road (this had been agreed already in the Paris Accords to be implemented in the 1950s but was brought forward). From now until the end of World War 2 the regions of Bohemia and Moravia that we now call the Czech Republic were known collectively as the “Protectorate” and integrated as a German state.

The Czechoslovak President, Edward Benes, and other government politicians had already fled abroad mostly to France and to Britain (those that were in France went to Britain when France was occupied). These leaders’ political campaign to represent Czechoslovakia’s interests was an uphill battle at first as western European powers still favoured the policy of appeasement at that time.

On October 28, 1939, which would have been the 21st anniversary of the Czechoslovak Declaration of Independence had Czechoslovakia not ceased to exist, popular celebrations turned into massive demonstrations of protest against the German occupation. A young medical student, Jan Opletal, was fatally wounded in the incident. His funeral, on November 15, 1939 turned into yet another spontaneous demonstration. In 1939, the Nazis reacted to the student demonstration by sentencing nine student leaders to death on November 17th (fifty years later, on November 17th 1989, a march by students to commemorate this event helped bring about the fall of Communism), by closing the Czech universities and by sending some 1,200 university students to concentration and labour camps. The Nazi regime was very cruel and strict and active resistance was harshly punished. Not surprisingly then, the Czech and Slovak resistance movements were small. Yet they were very dedicated, very determined, and often surprisingly successful, especially in the field of sabotage.

By July 1940, however, Great Britain recognized President Benes as the leader of the provisional “free Czechoslovak government in exile.” In addition to the London centre of the provisional government, the Moscow Communist centre (where politicians who favoured the Soviet political system had fled and included the future president Klement Gottwald) also played an important role in the Czechoslovak resistance movement during the war. Unfortunately, many of the Czechs and Slovaks who had chosen to go to Moscow spent at least part of the war years in Russian Gulags as suspected spies. Czechoslovak pilots in England’s RAF were particularly distinguished fighters (even if they were initially segregated from regular troops for the same reason) and they would play a fundamental role in the Battle of Britain.

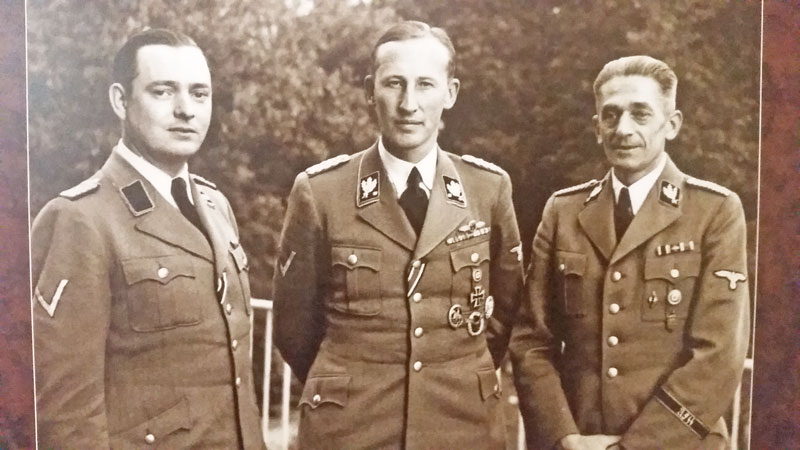

During the war, Czechoslovak army units fighting abroad often parachuted foreign-trained Czech and Slovak soldiers into occupied Czech territory to perform special assignments. The most significant of these special assignments was the assassination in 1942 of Reinhard Heydrich, the German Deputy Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia and one of the architects of the “Final Solution.” Amazingly he survived the bomb blast that destroyed his car but was poisoned, possibly by the horse hair used to make the padding for the seats which lodged in his body as a result of the explosion. Read more on the Operation Anthropoid page.

His assassination by Czechoslovak parachutists on May 27, 1942 set off a reign of terror throughout the Czech lands. A former Czechoslovak member of parliament called Karl Herman Frank had become head of the SS Police in Prague. He declared Martial Law and the Nazis conducted house-to-house searches looking for the parachutists and the members of the Czech resistance movement who had helped them. More than 1,600 people were executed and more were sent to concentration camps in the period immediately following the assassination.

The terror reached its height with the annihilation of the village of Lidice, where 173 men were executed and the women and children of the village were sent to concentration camps. Read more about that on the Lidice Memorial page. A few weeks later, the village of Lezaky, where the Nazis killed 54 men, women and children, was also razed to the ground. By the time this terror, known as the “Heydrichiada”, was over, the Nazis had damaged the resistance movement so much that it was only able to resume its activities at the very end of the war.

The resistance movements in Czechoslovakia culminated in the Slovak National Uprising of 1944 (which was brutally put down) and in the Prague Uprising in May of 1945 which started just a few days before Soviet forces arrived to officially liberate the city on May 9th. Also read about the Scottish connection and the accidental Bombing of Prague in February 1945.