Slav Epic Part One – Introduction and Location

The Slav Epic is a huge piece of work whether you look at it from a perspective of the number of paintings i.e. twenty, the size of the paintings (6 of the paintings would cover the front of a terraced house in England, including the roof), the historical context of the paintings or just that this was a work of more than a quarter of a century for the planning and execution. Later when I talk about events in Bulgaria and Hungary etc you’ll think what has this got to do with Czech? Remember that it’s the Slav Epic, not the Czech Epic. In fact it is so epic that I’ve deliberately had to split this topic into five posts.

This Part One post will tell you:

- Where it is right now.

- How Alfons Mucha develops the idea for the Slav Epic.

- Who Sponsored it.

- Where it was painted.

- Why the style of the Slav Epic is so different from his previous work.

- The order in which it was painted.

- The order in which it should be viewed.

- Where it’s been exhibited.

- Who owns it and the link to Moravsky Krumlov.

- Core interpretation.

In Slav Epic Parts Two to Five (links below) we take a look at all 20 paintings (5 paintings per part) in the Slav Epic in the order that they should be viewed. It tells you the historical context of the works, what details to look for and any hidden info.

Where is the Slav Epic?

Currently the Slav Epic is on display at the Moravsky Krumlov Castle.

Where Did the Slav Epic Idea Come From?

When Alfons Mucha finished his formal art education in Paris in 1889 he became just another artist struggling to find his own unique style and pay the bills at the same time. This required him to take a popular artistic route, the illustration of books and magazines. In 1890 he won a commission to illustrate some of the most famous European battles. If nothing else it propels Mucha’s work to the attention of more people. So if that wasn’t the seed for the Slav Epic then an event in 1894 certainly looks favourite. That year Mucha was commissioned to illustrate a book in French called “Scenes from the History of Germany”. This was something that Mucha could literally envisage in a version of Slavic History.

The Mini Slav Epic

When the Paris EXPO was held in 1900 Mucha put forward an idea for a set of murals that would depict the suffering of the Slavic people under oppressive rule. Basically this was to be a mini Slav Epic but the Austrian government, who were sponsoring the Austrian Empire part of EXPO, wanted something more peaceful. This undoubtedly confirmed that his artistic future would not be sponsored by the state so he would have to look elsewhere.

The Sponsor and Where it was Painted

In 1904 Mucha travelled to the USA primarily in search of a sponsor but also to make contacts and include some teaching roles as he was already well known. He would be in and out of the USA until in 1910 a very wealthy Slavophile called Charles Richard Crane agreed to sponsor the project. Part of the sponsorship covered the rental of a studio at the Zbiroh Chateau where all of the Slav Epic was created. The chateau has a collection of staging photographs taken by Mucha at that time as part of an exhibition.

The Mucha Museum in Prague

There are no actual paintings of the Slav Epic hosted at the Prague Mucha Museum but they do have a number of photographic studies that Mucha used to develop the characters, content and scale of the Slav Epic paintings.

Why is this work so different from previous work?

You have to remember that Alfons Mucha found fame in Paris doing illustrations for books and magazines initially. Then he linked up with Sarah Bernhardt and began drawing advertising posters. It’s his “poster” work that is most associated with his artistic style and individual characters in the Slav Epic do sometimes copy that style. But the Slav Epic is largely what I call the extension of the “mad staring eyes” phase. The Slav Epic was preceded by his decoration work at the Municipal House in Prague where you really begin to see the dark side, his turning towards the National Revival and the suffering of the Slavs.

In Order of Painting

So here were the first 12 paintings of the Slav Epic. The year is displayed first followed by it’s position in the final series in brackets.

- 1912 (1) The Slavs in their Original Homeland

- 1912 (2) The Celebration of Svantovit

- 1912 (3) Introduction of Slavic Liturgy into Great Moravia

- 1914 (14) The Defence of Sziget by Nikola Zrinski

- 1914 (15) The Printing of the Bible of Kralice in Ivancice

- 1914 (19) The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia

- 1916 (7) Milic of Kromeriz

- 1916 (8) Master Jan Hus Preaching at the Bethlehem Chapel: Truth Prevails

- 1916 (9) The Meeting at Krizky

- 1916 (11) After the Battle of Vitkov

- 1918 (12) Petr of Chelcice

- 1918 (16) Jan Amos Komensky

Mysteriously there were then two separate exhibitions, one at the Prague Klementinum in 1919 and the second in Chicago in 1920. Neither had more than 12 of the paintings because that was as many as had been painted at that time. It must have been like reading a book with a few chapters missing. It marks a 5 year break in the creation of the Slav Epic probably because Mucha was in demand in the new Czechoslovakia. Then we continue.

- 1923 (4) Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria

- 1923 (13) The Hussite King Jiri of Podebrad

- 1924 (5) King Premysl Otakar II of Bohemia

- 1924 (10) After the Battle of Grunewald

- 1926 (6) The Coronation of Serbian Tsar Stepan Dusan

- 1926 (17) The Holy Mount Athos

- 1926 (18) The Oath of Omladina under the Slavic Linden Tree

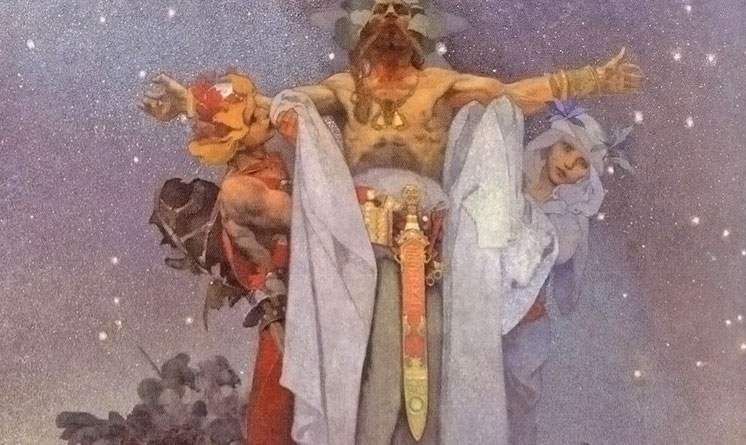

- 1926 (20) The Apotheosis of the Slavs, Slavs for Humanity

Gift to the Nation and Who Owns the Slav Epic

The Slav Epic as we know it today was completed in 1927. Alfons Mucha and his sponsor Charles Crane gave it as a gift to the City of Prague for the Czechoslovak people. This was in 1928 and coincided with the 10th anniversary of the creation of the Republic of Czechoslovakia.

The question about who owns it depends on a “condition”. When the Slav Epic was given to Prague it was done so “on condition” that a structure be built in the city “for the express purpose of displaying the Slav Epic”. So there’s the heart of it. Although the Slav Epic is “administered” by the Gallery of the Capital City of Prague, the ongoing legal argument is that “ownership” remains with the living heirs of Alfons Mucha until Prague builds the dedicated building. In that case the current heir called John Mucha wants the Slav Epic returned to Moravsky Krumlov. In another legal slight of hand, in 2010 the Slav Epic was listed as a movable Cultural Monument which had a direct effect on where the Slav Epic is located as you’ll see. Moravsky Krumlov comes up a lot in the ownership argument so it’s worth understanding the link.

What is the Link to Moravsky Krumlov?

In 1943 the decision was made to move the Slav Epic from storage in Prague to the Slatinany Castle in Moravia for safekeeping. That meant safekeeping from bombs, not from damp conditions. When the Slav Epic was inspected in the 1950s, several of the paintings had received atmospheric damage. The entire collection was to be moved to Alfons Mucha’s birthplace of Ivancice in Moravia for restoral but no building existed in the town that was suitable for the work. That’s when the adjacent town of Moravsky Krumlov offered the use of it’s castle.

So depending on your view of “ownership”, the Slav Epic was technically “on loan” to the Moravsky Krumlov Castle between 1963 and 2011. In 2010, following the Slav Epic’s listing as a “movable cultural monument”, this meant that the Gallery of the City of Prague could now administer the whole collection regardless of it’s location. A process started whereby the whole collection was gradually relocated from Moravsky Krumlov for display at the Trade Fair Palace building in Prague where it was exhibited between 2011 and 2016. The picture above is the entry ticket in 2012 when I visited with my family, 2 adults, 2 children and one baby (free).

Slav Epic on the Road

Only the Moravsky Krumlov Castle and the National Gallery Trade Fair Palace in Prague have exhibited the entire 20 painting Slav Epic series. Exhibitions before 1939 or in other countries have only been part of the collection.

Core Interpretation

Several themes will be present as you go through the Slav Epic series. Here are the most common:

Boy and Girl: Unless it’s an obvious family picture then you expect some kind of separation between them. The boy will signify a choice of war, the girl is peace.

Mother and Child: These characters will be looking right at you. They signify the acceptance of fate or change and inter-generational struggle.

Boy and Man: Similar to Mother and Child above, it’s usually a boy with a much older and possibly blind man. A sign both of compassion and inter-generational struggle.

The Linden Tree: As well as the Czech National Tree it is the symbol of longevity and signifies the long-term survival of the Slavs.

Girl with Flowers: Often this will be a ring of flowers around the head it signifies the continuance of Slavic traditions.

Slav Epic Position and Viewing Order, Click Link for that section.

Slav Epic Part Two – Paintings 1 to 5

1912 610×810 The Slavs in their Original Homeland

1912 610×810 The Celebration of Svantovit

1912 610×810 Introduction of Slavic Liturgy into Great Moravia

1923 405×480 Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria

1924 405×480 King Premysl Otakar II of Bohemia

Slav Epic Part Three – Paintings 6 to 10

1926 405×480 The Coronation of Serbian Tsar Stepan Dusan

1916 620×405 Milic of Kromeriz

1916 405×480 Master Jan Hus Preaching at the Bethlehem Chapel: Truth Prevails

1916 620×405 The Meeting at Krizky

1924 405×480 After the Battle of Grunewald

Slav Epic Part Four – Paintings 11 to 15

1916 405×620 After the Battle of Vitkov

1918 405×620 Petr of Chelcice

1923 405×480 The Hussite King Jiri of Podebrad

1914 610×810 The Defence of Sziget by Nikola Zrinski

1914 610×810 The Printing of the Bible of Kralice in Ivancice

Slav Epic Part Five – Paintings 16 to 20

1918 405×620 Jan Amos Komensky

1926 405×480 The Holy Mount Athos

1926 420×620 The Oath of Omladina under the Slavic Linden Tree

1914 610×810 The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia

1926 480×405 The Apotheosis of the Slavs, Slavs for Humanity

Next: Slav Epic Paintings 1 to 5