Film Review – Kolja

Have you got Netflix? This is a post about a Czech film called Kolja that won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film in 1997 and is available on Netflix. I first saw this film in it’s original language i.e. Czech but with French subtitles (because I was in France at the time). Strange to be writing about it 24 years later but I’ve seen it several times since and so long as you are prepared to read English subtitles you’ll find it’s a wonderful film that also shows you just a peek at what life was like here in the late 1980s under communist rule. In Czech it’s pronounced “koll-yah” and sometimes you see this film called “Kolya” but in any case it’s the friendly way to call somebody whose given name is Nicholas.

Setting the Scene

It’s 1989. The main character in the film is Mr Louka (Frantisek or just Franta to his friends) who is a cellist and has at some point played at the Rudolfinum with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra. In the last three years something has changed so he can no longer be part of the orchestra but he has not told this to his mother. He’s in his mid-fifties and living a single man’s life in Prague.

Communist Themes

Throughout the start of the film you’ll note that he’s scratching around for money. He’s playing music mostly at funerals and he has a few odd jobs on the side. You’ll learn that the reason for this is that his brother “emigrated” i.e. left the country illegally so Mr Louka was punished by the communist regime and blacklisted from performing or teaching. However you’ll see that his professional colleagues are still getting him some work giving private music lessons.

There’s a scene where the landlady of the house asks Mr Louka to put his flags out. Even now on the entry of buildings you see little flag holders where on one side you would have seen the Czech Flag and on the other side the Soviet Flag. People who lived in the apartments also had to stick the flags in their windows and buildings “competed” with each other. Mr Louka berates himself for not even being able to do a little protest like not sticking the flags. He has to do it or the landlady will be in trouble. Later when he has more money he pays his debt to the landlady he leaves a tip of CZK20. In todays money that is 1 US Dollar. But in 1989 that was 20 trips on public transport or 5 pints of beer. So you can see why she looks a bit shocked at the generosity.

In one scene his mother says that his brother Vic is doing well in the USA and there’s a little ill will at the situation this has caused Mr Louka. His mother is blissfully unaware of the communist reprisals. It’s mentioned that Mr Louka had to “buy out” his brother. This applies to the fact that having illegally emigrated, the communists could have claimed half the house where his mother lived and allow a complete stranger to live there. This was easier to do if the house was laid out in a way that could be divided into two apartments. Mr Louka went into debt to allow his mother to keep the whole house.

A friend of Mr Louka suggests a way to make money to settle most of his debts i.e. marrying. In 1989 a Russian could not travel to West Germany without special permission. However, a Russian with Czech papers could, so the easiest way to get those papers was for a Russian Girl to marry a Czech man or vice-versa. This happened frequently enough for the authorities to get involved and you’d be looking at a prison sentence if caught.

The communists kept a safeguard in that it was made known that if somebody “emigrated” without permission then their family would suffer. In our case, the Russian girl skips the country but leaves her 5 year old son “Kolja” behind and circumstances happen that Mr Louka has to look after the child. So there you have the two themes of the film 1) a man getting by despite communist reprisals and 2) a single man forced to look after a 5 year old child who speaks a different language and the challenges it brings.

Towards the end of the film you are introduced to the Czech officialdom, the police investigating Mr Louka, the woman managing the fate of the child. Note that these are Czech people, not Russian but so integrated into communist thinking that they may as well be. You’ll see the security police (StB) again shaking their keys as part of the demonstration, mingling with the crowd and noting who was protesting (jingling the keys is a traditionally Slavic way of telling someone to pack up and clear off). This alludes to the fact that post-revolution the StB, although dissolved, faced no personal repercussions even though they had wrecked lives.

At the end when protests are happening you hear talk of the “resistance” about how it was too late to start. Note that people all over the country could listen to what was happening in Prague but could not see it hence many people really did not realise that communism in the country was finished for at least another few weeks. Throughout the film you will have seen characters just going about their day to day lives, nothing political. Post 1968 many people were ejected from the country but the “resistance” were the people throughout the 70s and 80s who stayed, educated people who had to accept a life of persecution by the authorities.

And so the end of the film brings an end to communist rule and the beginning of a return to freedom. I hope you enjoy it.

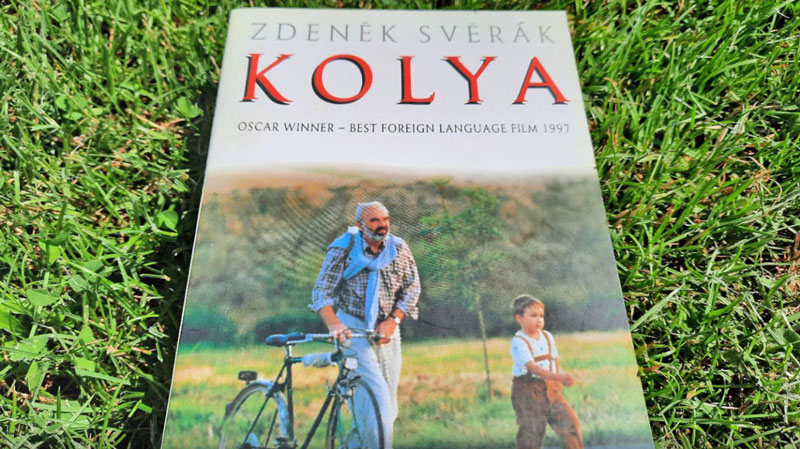

The Book

It’s a nice film but if you can’t see your way to reading subtitles then you might be interested to know that Kolja has also been released as an English language paperback. ISBN 0-7472-5894-5.